Millions of the world’s poorest people will face devastation from today’s rocketing food prices because the global food system is fatally flawed and policy-makers can’t find the courage to fix it. Policy-makers have taken cheap food for granted for nearly 30 years. Those days are gone.

Developing countries are bracing themselves for the worst effects of rising corn, soy and wheat prices on their poorest people. One of the worst hot-spots is Yemen which is heavily dependent on food imports, including for 90% of its wheat, and where 10m people are hungry today and some 267,000 children at risk of death from malnourishment because people can’t afford what food there is. Families are exhausting their options to cope, including instances of marrying off young daughters in order to have one less mouth to feed.

The world’s is already witnessing a record number of food-related emergencies. The UN estimates that some $7.83bn is needed to respond to food-related crises in the Sahel region of West Africa, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Yemen, but to date only $3.73 billion has been pledged by donors, representing a shortfall of $4.1bn. With the international response slowed by the global economic crisis, rising global food prices could pile more pressure on an overstretched humanitarian system.

Other fragile populations around the world, living on or near the poverty line, will be dragged under by price spikes and volatility. Nearly a billion people are already too poor to feed themselves, so any long-term food spike is guaranteed to trap millions more who are now just “getting by”, into poverty. Worrying too is the continuing drop in global corn stocks that are now at their lowest levels for six years .

There are important differences and similarities between the food crisis of 2008 and today. In 2008 oil prices were about 30% higher and the global price of rice also spiked (which is not the case today). There was also damaging commodity speculation in 2008 – which could yet be happening again now. In both periods, US and EU biofuels mandates played a major role in artificially inflating prices. This year the crisis has been sparked by droughts in the US (the world’s largest exporter of soy, wheat and corn) and elsewhere that are fully consistent with climate change projections.

While we can already map where problems might occur in 2012, there are many variables and it is too early to say exactly when and how these price hikes will play out for everyone. A lot will depend on how fast and smart policy-makers – especially those in the G20 – react over the coming weeks and months. But their track-record is poor and does not inspire confidence.

History is repeating itself and will keep doing so until we tackle the fundamental weaknesses that keep a billion people hungry and threaten to make many more hungry. We must stop the obscene waste of food including burning it as biodiesel in our trucks and cars. We need to tackle climate change, forced acquisition of land (commonly termed land-grabs) and damaging speculation. We must build up our food stocks and kick-start good investment once more in small-holder farmers and in resilient, sustainable agriculture.

What’s gone wrong in 2012?

The United States has been hit by its worst drought in 60 years. As of July, 88% of the US corn crop was growing in regions affected by drought. Drought is also affecting other crops and forms of agriculture: 44% of US cattle production and 40% of US soybean production are in severe drought areas too. US soy yields might still be able to recover if timely rains occur – though prospects seem dim.

Russia’s grain harvests – mostly wheat – have been hit by dry weather this year, in addition to severe flooding in the south that caused major damage to unpicked and stored grain. Although harvests are expected to cover domestic demand, it is likely to have significantly less to export this year. Fears that Russia may institute an export ban are currently being denied.

Ukraine and Kazakhastan have also been hit by dry weather which will hit their harvests – principally maize in Ukraine (Ukraine was the world’s third largest exporter in 2011) and wheat in Kazakhstan, though recent rains in Kazakhstan may help. India is experiencing monsoon rains – the main source of irrigation for 55 per cent of its farmlands – that are 19% below average, with harvests expected to be significantly down from recent years. Bumper stocks on the back of bumper harvests in 2010 and 2011 provide a cushion. Thus far the government does not envisage an export ban. Australia, a significant exporter of wheat, has cut its wheat forecast by 2 million tonnes between March and June 2012 due to moisture stress in the state of Western Australia.

Climate change is a steadily worsening contributing factor, as predicted: This record-breaking US drought is fully consistent with scientific projections that climate change will mean increasingly arid conditions and drought in this region . Those projections suggest persistent severe droughts across the central US in future decades. May was the 327th consecutive month in which the global temperature exceeded the 20th century average. The US experienced 14 billion-dollars of disasters in 2011 – an historical record – including a blizzard, tornadoes, floods, a hurricane, a tropical storm, drought and heatwaves, and wildfires. In 2012 it has already experienced horrifying wildfires, a windstorm that hit Washington DC, heat waves in much of the country, and a massive drought, according to Christopher Field, a lead author of the IPCC report and director of global ecology at the Carnegie Institute for Science.

Biofuels have been a major factor in both the 2008 and 2012 crises: The US Renewable Fuel Standard mandates 15.2 billion gallons of biofuels for 2012, up to 13.4 billion gallons of which can come from corn-based ethanol. The legislation requires that up to 15 billion gallons of domestic corn ethanol be blended into the US fuel supply by 2022. In 2011 the fuel industry took 40 per cent of the US corn crop. It could be that this year a higher share of the US corn crop will be taken up by biofuels – which would keep corn prices very high. There is increasing political opposition in the US to the mandate.

The oil price is a relatively more benign influence this year: Generally, the world’s poorest countries spend about 2.5 times more money importing oil than they do food. However oil prices spiked in 2008 to an all-time high of $145 a barrel, inflating the cost of food transport and fertilisers and hitting the balance of payments for non oil-producing developing countries – meaning they had less money to buy food. Today however oil prices are lower, around $100 a barrel. If oil prices did rise much higher it would worsen today’s rising food prices as well as restricting output of other goods too.

But the US exchange rate is more problematic this year: In 2008 the dollar was trading lower than today (in April 2008 it was $1.55 against the euro, $1.98 against the pound, while in July 2012 it was $1.23 against the euro and $1.56 against the pound). The higher the dollar value, the more it costs food-importing countries to buy their food – so in general it’s worse for them in 2012 than in 2008.

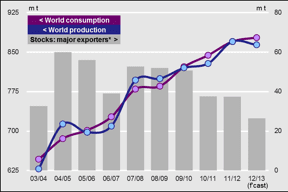

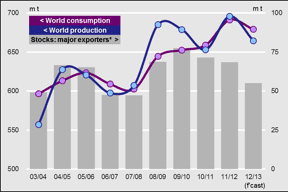

Food reserves are expected to fall to dramatically low levels. Despite last year’s record production levels for wheat, corn and rice, stock levels for corn and wheat this year are expected to reach such low levels that prices become very sensitive to disturbances in supply. In the US the corn stocks are expected to be historically tight and equal to only about three and a half weeks of supply.

Financial speculation on commodity markets. Most people now agree that we need to regulate commodity markets in order to improve transparency and stop excessive speculation. But we’re still waiting, especially in the US and the EU. Studies show that the drought in the US may trigger a speculative bubble with prices rising well beyond the increase justified by the drought (and potentially crashing back down in the future) . Beyond remedial moves to limit the amount of corn converted to ethanol, we need better regulation of commodity markets and financial speculators.

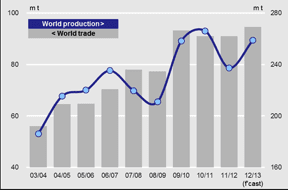

More than 80% of the exports of major grains come from five countries and are controlled by four major companies. This makes international markets very vulnerable. The United States is the world’s largest exporter of corn, soybeans and wheat, and price spikes in the crop sector will ripple through markets globally. Global futures corn prices have increased by 45 per cent, soybeans 30 per cent and wheat 50 per cent since June, according to the World Bank. Rice, however, remains plentiful, with prices falling by nine per cent so far this year .

These hikes will eventually lead to a rise in meat prices (corn and soy are the main constituents in animal feed). For countries that rely on food import such as Yemen – which imports 90% of its food – higher international food prices mean higher import bills also affecting balance of payments. For poor households who spend much of their income on food a rise in food prices may have devastating effects on household budgets leading to long term effects on health, education, and life chances.

Consumers will likely see impacts within two months for beef, pork, poultry and dairy (especially milk). The full effects of the increase in corn prices for packaged and processed foods (cereal, corn flour, etc.) will likely take 10-12 months to hit retail food prices.

The drought is likely to hit retail prices for beef, pork, poultry, and dairy products, later this year and into 2013. But in the short term, drought conditions may lead to herd culling in response to higher feed costs, and short term increases in meat supply. This could decrease prices for some meat products in the short-term. But that trend would reverse over time after product supplies shrink.

Cargill CEO Greg Page has said “If all of that (demand rationing) is only on livestock or food consumers, it really makes the burden disproportionate. What we see are 3 or 4 percent declines in supply leading to 40 to 50 percent increases in prices.

What does this mean for developing countries?

Soy and corn are important animal feed stocks, so meat prices are likely to rise, as well as milk and eggs. Poor people in Mexico and Central America, where maize is a staple food, may be affected. Bread will go up in North Africa because wheat prices tend to follow maize prices.

Higher and volatile prices will affect consumers living in countries that rely heavily on international markets as well as those that have had a weak harvest. While food price increases clearly present a major threat to poor consumers, they may provide an opportunity for poor farmers. Most of the poorest people in developing countries make a living from agriculture, so higher prices could offer them a better livelihood. However, many are unable to take advantage of high food prices, especially when these remain unpredictable, for instance because they have limited access to land and water and to agricultural investments, weak rural economic infrastructure such as irrigation channels, or face the persisting effects of disasters and conflicts.

China: meat (particularly pork) requires large soy imports so China could see a rise in meat prices but it has a substantial soy reserve and huge currency reserves, so can mitigate impact. Otherwise China is self-sufficient in rice and wheat. In Latin America: Mexico, Central America and the Andes are most likely to be affected by higher corn prices brought about by higher prices of US corn (mainly by transmission of prices, because they mostly grow a different kind of corn than the US – but reduced quantities and higher costs of US corn will “infect” all maize markets). North Africa & Middle East: countries in North Africa and the Middle East which are dependent on wheat imports, such as Yemen and Egypt, will be the most vulnerable to higher international prices. However a good reported harvest in Egypt should ease pressure on Egypt though it’s reported that Morocco has had a poor harvest. Sub Saharan Africa is a mixed picture – even within countries there are pockets that are heavily dependent on food imports (i.e. cities) whereas rural areas can be relatively isolated from international markets so no major impacts are predicted as yet. Countries in the inland Sahel region are generally less affected by these price increases because they tend not to import grains from international markets. In 2008, food prices deeply struck the coast but behaved more moderately in the Sahel.

Experience shows that international price changes take months to pass through to West Africa. A good West Africa crop could ‘protect’ the region from international price increases; a poor harvest would imply that the region would be more exposed to international price risk. The main harvest will begin in a few weeks (i.e. end August). We know that the ‘western basin’ countries i.e. Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia are most exposed to international price rises.

Food aid may be affected. Firstly, the increase in prices will affect the amount of food that the World Food Programme can buy. Secondly, the US government (the largest contributor to food aid) is likely to be able to buy less food, either bilaterally or through the WFP. In 2010, more than 55 percent of the food aid products the US bought were derived from corn, wheat or soybeans. Increases in the price of these commodities will have an impact on the amount of food aid the US is able to purchase. Corn-soy blend is already an expensive food aid commodity and is considered to be a primary product for use to prevent (and sometimes treat) malnutrition. Increased corn prices can thus be expected to hit the US’s ability to deliver more nutritious food products. It is too early to tell however what the exact impact will be.

Rae Allen" />

Rae Allen" />