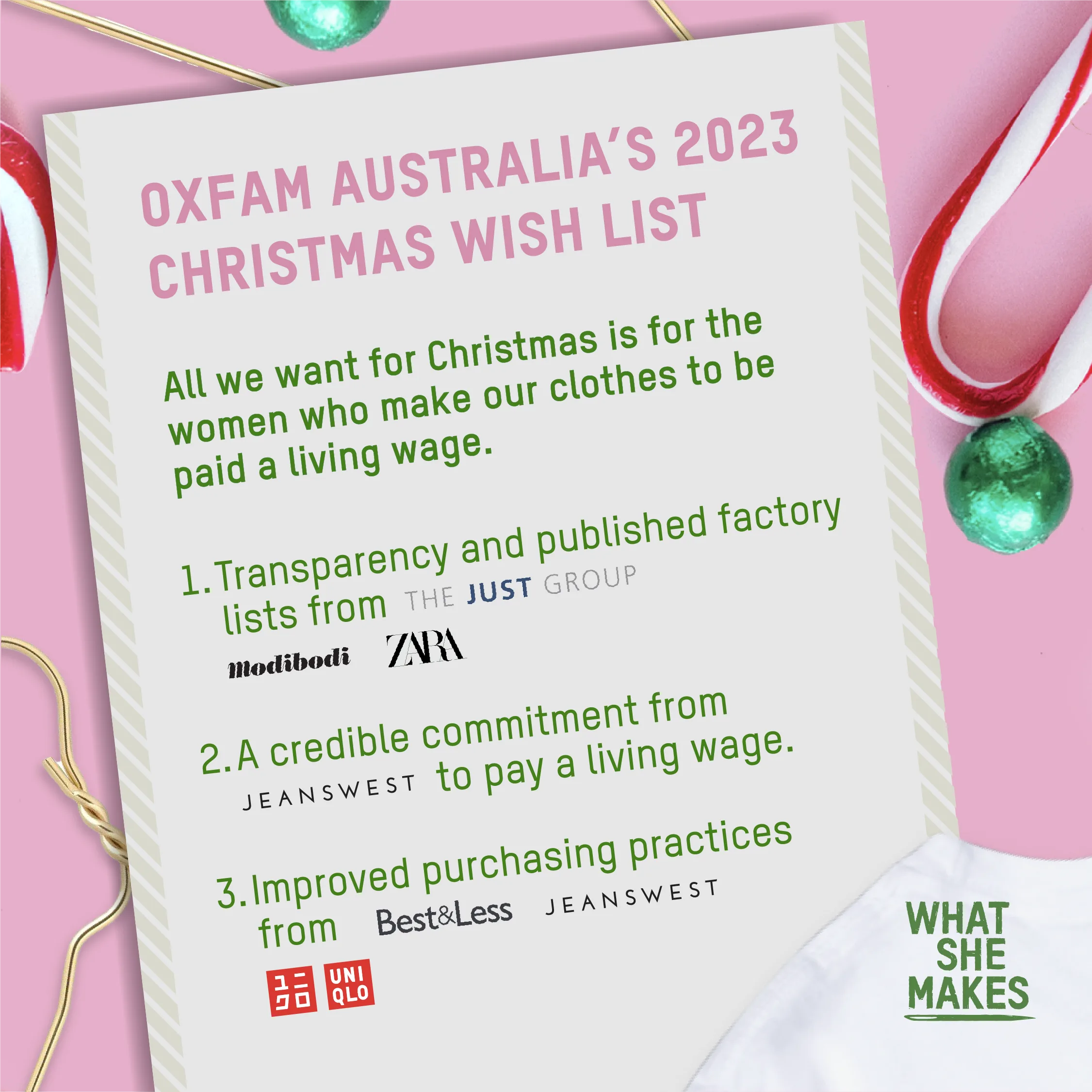

Oxfam Australia’s 2023

Christmas Wish List

All we want for Christmas is for the women who make our clothes to be paid a living wage. But most are not paid enough to cover basic life expenses like food and healthcare, which keeps them in poverty.

Our Christmas Wish List includes brands that are lagging behind on their journey to pay a living wage.

We’re calling on brands to be transparent about where their clothes are made, make real commitments to paying the women who make our clothes a living wage and improve how they do business. And you can stand with us.

Why are these goals on our Christmas Wish List?

1. Transparency and published factory lists

The Just Group, Modibodi and Zara hide where our clothes are made. These brands are lagging behind industry standards for transparency, which makes it harder to hold them accountable to their workers.

Many brands who don’t share their factory locations cite concerns about intellectual property. But, with more luxury brands than ever disclosing their factory lists1 and many sports and high-performance brands sharing the factories where their clothes are made, we feel these concerns don’t hold up.

2. A credible commitment to pay a living wage

Paying the minimum wage is not enough. Fashion brands need to be paying – or be on a journey to pay – living wages.

All the brands in the What She Makes campaign have made a creditable commitment, with milestones, to pay a living wage – except Jeans West.

We demand that Jeans West make a credible commitment to pay a living wage.

3. Improved purchasing practices

How brands do business influences what workers are paid. Ruthless purchasing practices and unrealistic expectations from brands result in low wages for the women who make our clothes.

Many factories struggle to enforce realistic boundaries with brands when they’re negotiating prices. This is due to the risk that brands might take their business elsewhere.

One thing brands can do to improve wages is separate and protect the cost of wages during price negotiations. This means that negotiations about reductions in price don’t have to come at the expense of wages. This practice, known as separating labour costs or ‘ring fencing’, involves making wages an itemised part and is a crucial form of protection for workers.

Best & Less, Jeans West and Uniqlo are lagging behind other big brands in committing to separating labour costs in their supply chains.

Stand with the women who make our clothes

Make our Christmas wishes come true and tell these brands to clean up their act. If enough of us speak up these brands won’t be able to ignore us. Copy and paste these messages to share on their socials:

Hey Just Group, share where your clothes are made! #WhatSheMakes #OxfamWishList

Post on JustJean’s InstagramHey Modibodi, share where your clothes are made! #WhatSheMakes #OxfamWishList

Post on Modibodi’s InstagramHey Jeans West, protect wages in price negotiations! I care about #WhatSheMakes #OxfamWishList

Post on Jeanswest’s InstagramHey Best & Less, protect wages in price negotiations! I care about #WhatSheMakes #OxfamWishList

Post on Best&Less’ InstagramHey Uniqlo, protect wages in price negotiations! I care about #WhatSheMakes #OxfamWishList

Post on UNIQLO’s InstagramSabina’s story

“I am 35 years old. I got married at the age of 15 when I was in 9th grade. I gave birth to three children at a young age, then their father left. I left three children at home and started working in the garments as a helper.”

Without overtime Sabina’s salary is about AUD$130, with overtime (gruelling eleven-hour days) it is about AUD$210, per month

Even with overtime, her wage isn’t enough to cover her family’s living expenses which has terrible consequences for their education and health care costs. The current living wage for Dhaka, where Sabina lives, is about $350 AUD.

Half of Sabina’s monthly wage goes to support her disabled son who is unable to work

“My elder son’s name is Nawshad. He is disabled and cannot walk. My second son is 17 years old. I am unable to give his exam fees due to financial problems. “

Her sons live back in the village with their grandparents while she must stay in the city for work. After other expenses like rent there is very little left for even the essentials like enough nutritious food or healthcare.

“I go through hardship. I have borrowed from the store. I don’t borrow that much, because I cannot repay, so I don’t borrow in fear.”

Sabina is also fearful of abuse in her workplace

Unreasonable targets lead to a culture of harassment and unsafe work with limited access to drink, food and toilet breaks.

“Due to the target filling pressure, sometimes I can eat and sometimes I cannot. It’s hard to drink water and use the toilet. Yes, they abuse [me], but if I meet the target, then they don’t abuse. It happens to everyone.“

But Sabina has seen improvements in her workplace now they are organised with a union

“Abuse has decreased a little. There are union members that’s why they cannot abuse. They used to sack workers and beat and abuse them, but now they cannot. We have a union in our factory. When they are with us, no one can abuse us.”

Sabina has a very clear message for Australian’s who wear the clothes she makes

(Her factory manufactures for H&M so you may just be wearing something she’s made right now.)

“I want to give them a message that, we want to thank them as they happily wear our clothes.

We are happy in their happiness. They should stand beside us, allow us to work, and if we get a higher wage, we will be happy. I want to tell them.

We feel happy when they buy the clothes we make and wear them. If we get some money, we can live happily.

If they give more work to Bangladesh, we can live peacefully. We want peace for them and us.”

Learn more about the brands on our Christmas Wish List

The Just Group is an iconic Australian company that includes brands such as Peter Alexander, Just Jeans, Jay Jays and Portmans. The Just Group has committed to pay a living wage and has milestones to implement supplier training and protect labour costs in price negotiations. But the Just Group still refuses to share where it makes our clothes.

Modibodi is a new Australian company making undies for periods and incontinence, and bras for breast feeding. Modibodi contributes to reducing period stigma and actively considers many different areas of sustainability in its business. Despite calling out transparency as an important sustainability issue, Modibodi still isn’t transparent with its consumers about where its clothes are made.

The quintessential fast fashion brand, Zara, has been under immense pressure to improve its business practices and conditions for the women who make its clothes. Zara has made a commitment to work towards paying a living wage and improving its purchasing practices, but it still refuses to share its factory locations.

In the past, Jeans West was committed to paying a living wage. However, when the company was in voluntary administration in 2020, many of its ethical sourcing policies were removed. It’s time for Jeans West to recommit to pay a living wage, so the women who make our clothes don’t have to live in poverty. As well as removing its commitment to a living wage, Jeans West has no commitment to separating labour costs, achieving better business practices with its suppliers, and ensuring the women who make our clothes are paid a living wage.

Last time Oxfam met with Best & Less, it was implementing systems to improve pricing transparency with suppliers, however the brand stopped short of committing to separating labour costs. Best & Less has not responded to requests to meet with us this year, nor updated any public commitments. Best & Less needs to commit to separating labour costs to improve its purchasing practices.

Uniqlo’s production arm, Fast Retailing, cites regular communication and ongoing relationships with factories as important steps it takes in promoting responsible purchasing. While these are good steps, as a major global player Uniqlo can do more. It should separate labour costs with its suppliers, because Uniqlo’s behaviour as a large brand impacts the industry as a whole.

Christmas at a glance

This might be our first Christmas wish list but it’s the fifth time we have called out the brands at Christmas since 2013.

The first year it ran, in the wake of the Rana Plaza disaster, we called on brands to sign onto the Bangladesh accord for safety – all but two of the brands on the tracker have now done this.

Thanks to tireless campaigning from workers, Oxfam, and supporters like you, brands have come a long way. You can have a look back on last year’s list here: