With greenhouse gas emissions at an all time high, and the world lurching towards a third food price spike in four years following the worst US drought since the 1950s, there is an alarming gap in our knowledge – how will an increase in extreme weather caused by climate change affect future food prices?

To date, research on food prices and climate change has looked almost exclusively at the averages: how gradually rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns will affect long-run average prices. It points to a future of higher food prices: Oxfam-commissioned research last year suggested food prices could double in the next 20 years; with up to half the increase caused by climate change (see also research by International Food Policy Reasearch Institute and Stanford University).

Alarming, but only half the story. Climate change will also lead to an increase in extreme weather, such as droughts, floods and heatwaves. As today’s US drought lays bare, extreme weather can wipe out harvests and drive up prices precipitously in the short term. But current research does not account for how these extremes might affect future global food prices. (Though there has been some regional analysis).

Oxfam felt it was time to have a go, so we commissioned some more research from the Institute of Development Studies. Published today, it uses CGE (computable general equilibrium) modelling to look at the impact of extreme weather scenarios on global food prices in 2030. CGE models have their flaws and are certainly not predictive instruments, but they do help us think through broad possible scenarios for whole systems.

The research highlights some top line trends that can plausibly be expected in a world of more frequent and intense weather extremes. While average prices could double by 2030, the modelling suggests that one or more extreme events in a single year could bring about price spikes of comparable magnitude to two decades of projected long-run price increases.

The research highlights some top line trends that can plausibly be expected in a world of more frequent and intense weather extremes. While average prices could double by 2030, the modelling suggests that one or more extreme events in a single year could bring about price spikes of comparable magnitude to two decades of projected long-run price increases.

The research suggests that in 2030 the world could be even more vulnerable to the kind of drought happening today in the US, as dependence on US exports of wheat and maize is predicted to rise, whilst climate change increases the likelihood of extreme droughts in North America. The US Department of Agriculture recently estimated that climate change could cost corn belt farmers between US$1.1 to $4 billion annually by 2030.

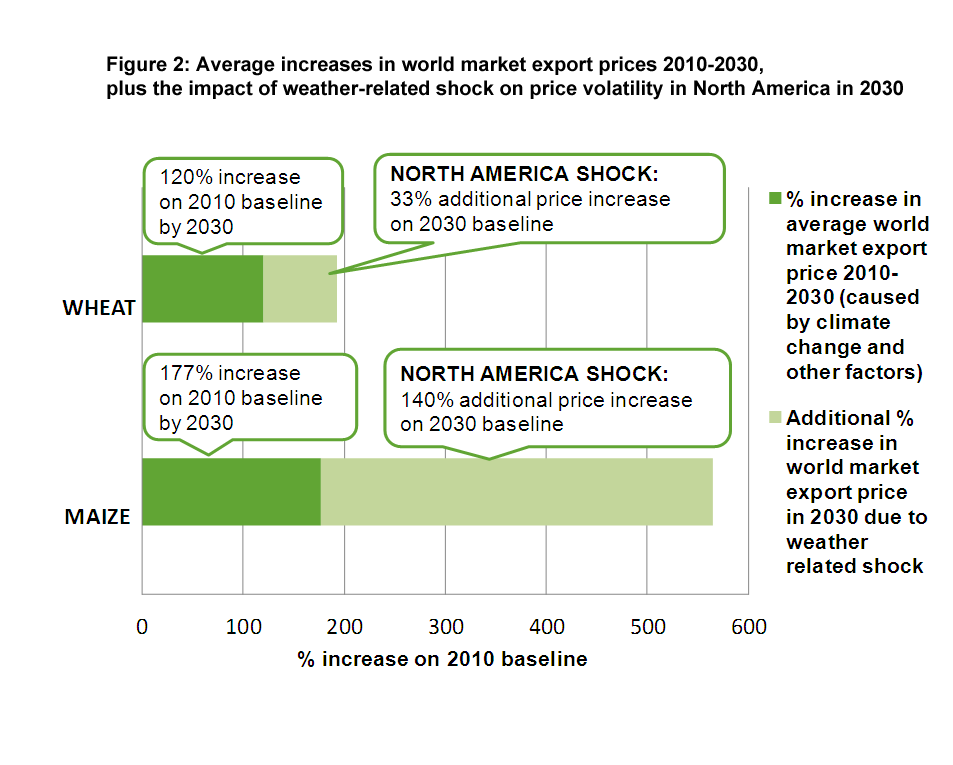

Even based on a conservative scenario, the modelling shows a drought of similar magnitude to the US drought in 1988 could raise the price of maize by as much as 140 per cent in 2030 (see fig 2).

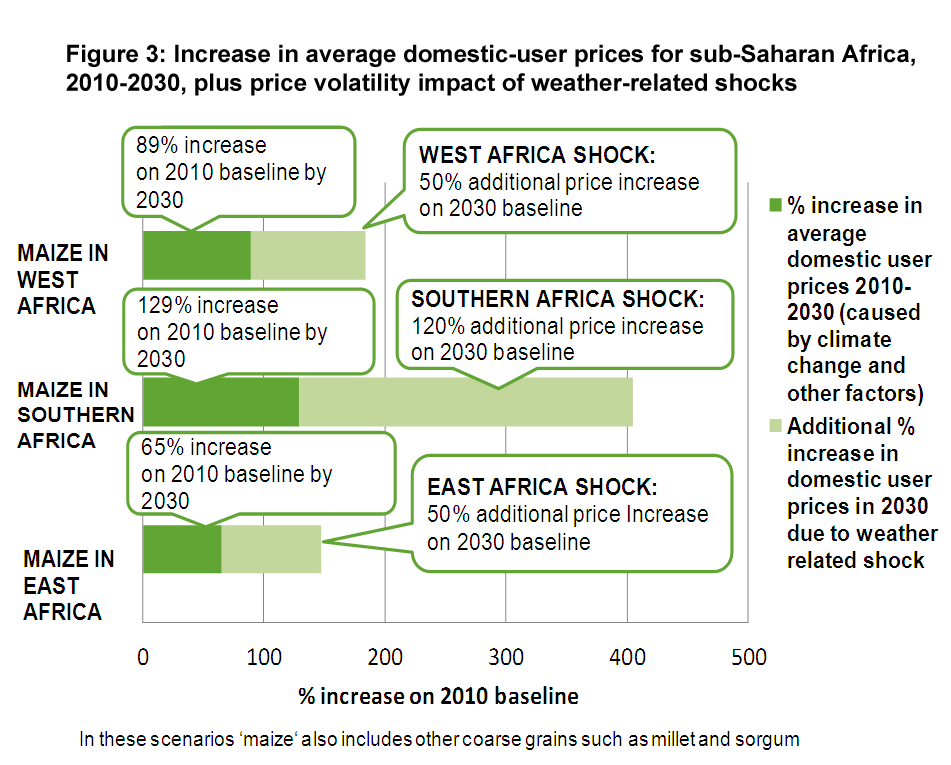

The modelling also shows dramatic impacts in sub-Saharan Africa in 2030 – the consumer price of maize and other coarse grains in southern Africa could increase by as much as 120 per cent, on top of already higher average prices (see fig 3).

Food security experts working on the next IPCC Assessment recently warned that governments should take more account of how weather extremes could affect food supplies. Because if the climate becomes increasingly erratic, food production and prices will too, with devastating consequences for the lives of livelihoods of people living in poverty.

Food security experts working on the next IPCC Assessment recently warned that governments should take more account of how weather extremes could affect food supplies. Because if the climate becomes increasingly erratic, food production and prices will too, with devastating consequences for the lives of livelihoods of people living in poverty.

Governments ‘stress-tested’ the banks after the financial crisis. Our global food system is also too big to fail, and needs stress-testing to fully assess and address its critical thresholds in relation to climate change. Stress testing would seek to understand feasible worst case scenarios and identify the levels, locations and likelihood of vulnerability that could occur.

This includes major crop producing regions most at risk; the impact of multiple harvest failures in the same year, as well as the cumulative impact of significant yield shocks becoming more common; impacts on food deficit low income countries; and interactions with other major threats to the food system, such as high oil prices.

This research is just one more contribution to the overwhelming case for action. The necessary policy responses are well documented: reducing emissions, adapting to climate change, and building the resilience of markets and people in poverty (see here, here, here and here).

The real unknown is how bad things have to get before we start to see concerted action.

Tracy Carty is Climate Change Policy Adviser at Oxfam GB