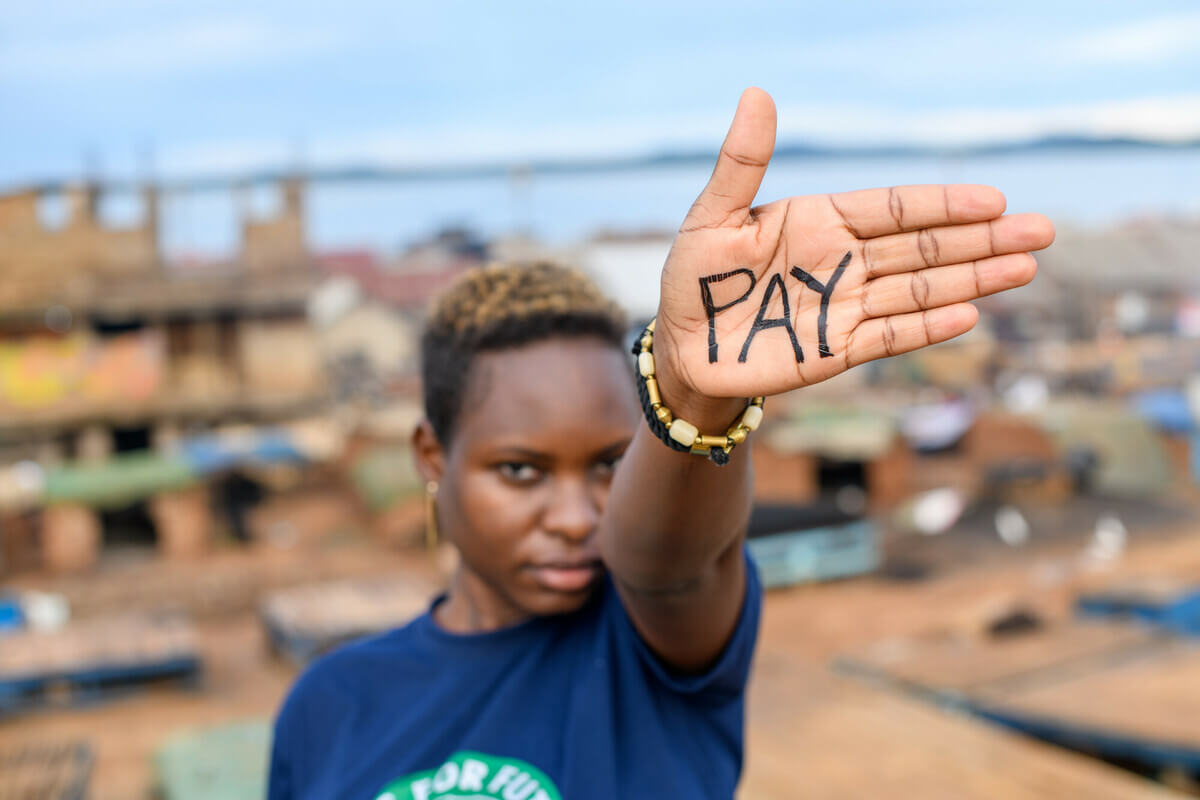

In the lead up the G20 Leaders’ Summit in November, Oxfam Australia CEO Dr Helen Szoke spoke at The Bob Hawke Prime Ministerial Centre in Adelaide about the threat posed by extreme inequality and the opportunity that tackling it represents.

Below follows an edited excerpt from Dr Helen Szoke’s speech.

Right now, we live in an important moment for the idea of equality. I don’t mean literal equality in which everyone has exactly the same income, wealth and power.

I mean, rather, the ideal of a world in which inequalities of such things are reducing, not increasing.

In which a far greater number of people could be considered broadly prosperous, with a democratic voice.

And in which billions of people’s life chances are not unduly limited by the circumstances of their birth.

It [equality] improves relative human happiness—and if human happiness is not our aim, we’ve gone wrong somewhere.

The case for equality is easy to make.

- It is good for growth—which lifts people out of poverty.

- It improves relative human happiness—and if human happiness is not our aim, we’ve gone wrong somewhere.

- And it appeals to human values of fairness that are buried deep in our being. The urge for equality cannot be written off as emotionalism or populism. It’s part of being human, as much psychological research now suggests.

Of course it’s easy to make a case for equality—but it’s a much harder thing to bring about.

Thanks to the growth in developing and emerging economies in recent decades, the number of people living in absolute poverty has declined, in some places dramatically.

According to the World Bank, the number of people in the developing world living on less than $1.25 a day reduced from about 1.9 billion in 1981 to 1.4 billion in 2008. That’s a drop from 1 in every 2 people to 1 in every 4.

And amazingly, the world reached the first target of Millennium Development Goal 1 – to reduce extreme poverty by half – five whole years ahead of schedule, in 2000.

It’s a magnificent achievement. One that has led many to ask whether we should be worrying ourselves about inequality at all. Why, some ask, are we wasting our time talking about inequality when the Asian miracle is happening?

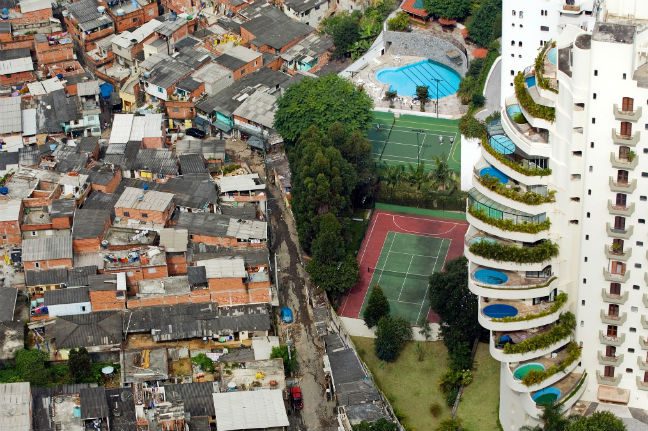

My answer is this: an explosion of wealth accompanied by a profoundly unjust distribution of that wealth has consequences.

Serious consequences.

It represents a lost opportunity to lift even more people out of poverty. And it is a potential source of injustice, resentment and conflict.

Recently, Oxfam’s researchers have uncovered a disturbing fact: While global wealth may be increasing, inequality is widening and doing so with spectacular speed.

Here are some statistics that are almost unbelievable in their scale but are true.

While global wealth may be increasing, inequality is widening and doing so with spectacular speed.

- Today almost half the world’s wealth is owned by just one per cent of the world’s population.

- The richest 85 people in the world own the same wealth as the poorest half of the world’s people. 85 owning the same as 3.5 billion. I find that absolutely staggering.

- Seven out of ten people live in countries in which economic inequality has increased in the last thirty years.

- And, new data just released by Credit Suisse shows that today the richest 10 per cent of people own over 87 per cent of the world’s wealth. 87 per cent.

This level of inequality can’t go on.

And this realisation is bringing about a change in the world of economic ideas.

After decades in which the idea of economic reform was dominated by the so-called “Washington Consensus” of smaller government, lower taxation and increased competition, the tide is swinging back in favour of redistribution.

In fact, in many cases, it’s the creators of the old consensus who are helping create a new one. The World Economic Forum, the World Bank, the OECD, the IMF, the Asian Development Bank and the Bank of England are belling the cat on inequality.

In May of this year, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, said that extreme economic behaviour is starting to break down the social contract within nations. At that same conference, IMF chief Christine Lagarde, characterised the world economy as one of ‘excess’ and ‘mistrust’, calling for growth to be more inclusive.

As Peter Hatcher wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald recently: ‘When Oxfam and the IMF converge on an agenda item, you know it’s gone beyond ideology.’

‘When Oxfam and the IMF converge on an agenda item, you know it’s gone beyond ideology.’

Political leaders, such as US President Barack Obama are listing inequality as the defining issue of our times. And religious leaders like Pope Francis are agreeing. So are some of the world’s leading intellectuals.

We saw this in Australia earlier this year with the rapturous reception given to the visit of Nobel Prize winning economist Professor Joseph P Stiglitz.

His argument? Equality works.

There is no doubt that, starting in the academy, and extending to the major decision-making bodies of the world, the Washington Consensus is giving way to a new consensus.

I call it The Equality Consensus.